Is a company accountable to its shareholders or stakeholders? Should maximizing shareholder or stakeholder value be a company’s governing objective? Should shareholder or stakeholder capitalism define our economic system? These questions are at the heart of a debate that often sparks other questions as well, such as: What is a company’s social responsibility? What is the purpose of the corporation? And what should be a company’s governing objective?

The debate started with the invention of public companies. This created a separation of ownership from management and sparked the fear that such companies were accountable to no one. The solution was to make management accountable to shareholders. The principle was to equate the rights of shareholders to the property rights of owners. And the thinking was that shareholders bore the risks and rewards of the company’s failure and success, and so they had corresponding rights to control it.

But right or wrong, this solution has never been wholly satisfactory because there are so many other constituencies – customers, employees, community, society at large - who have a “stake” in a company’s behavior and impact. Thus, was born the great shareholder-stakeholder debate.

Unfortunately, for business leaders, the debate generates a lot more political heat than practical light.

Here’s why.

There are two versions of “shareholder capitalism” floating around. In the first, “shareholder value” is the value today of all cash flows that a company (or product or business) is likely to generate for the rest of its life. Finance professors call this “net present value,” and Warren Buffett, the chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, calls it “intrinsic value.” By this definition, shareholder value is essentially a measure of the company’s future earnings power and ongoing investment needs and opportunities. It is also a proxy or synonym for its economic health – both today and for the long haul.

If this is “shareholder value,” what does “maximizing” it mean? It means consistently choosing those strategies that are most likely to yield the greatest future earnings power for the company, net of any investment those choices require. It demands that leaders never stop looking for better strategies, because they can never know with absolute certainty if there are higher-value ones than those they’ve considered so far.

This version of maximizing shareholder value does not tolerate two common problems. The first is “short-termism” such as cutting productive R&D or buying back shares to hit an earnings-per-share target. The other problem is the opposite of short-termism and it’s just as deadly: “long-termism.” This is the tolerance of luxurious investment, lax overhead, and low-balled targets. These behaviors put a company’s health at risk because they sap the profits that are needed today to invest for the future.

Finally, this version of maximizing shareholder value calls for companies to, as Wayne Peacock, CEO of USAA, says, “… do the right thing because it’s the right thing for shareholders.” He continues, “[This means] we have to take care of the employees and truly create the environment in which they can feel welcome and feel that they belong. [It means] we owe support in the communities where we work and live, as well. And I believe that today’s employees, and more so tomorrow’s, and tomorrow’s consumers, are going to demand that. [Finally, it means that] companies act in a socially responsible way.”

There is, however, a second, very different definition of shareholder capitalism. It treats “shareholder value” as a synonym for today’s stock price and “maximizing” it as putting short-term profits and current shareholders first. This is the version Jack Welch, the former CEO of General Electric, had in mind when he defined it as “setting a stock price goal” and famously called it “the dumbest idea ever.” It’s also the version Paul Collier describes in The Future of Capitalism, when he writes, “[it’s] a sole focus on the bottom line…[where] companies no longer feel responsible to their employees or the communities where they operate.” And the same for Roger Martin in his book Fixing the Game, where he calls it “tracking the company’s stock price on screens,” “distracting CEOs with stock-based compensation,” “spinning lines to shareholders,” and “trading long-term…value for temporary gains.”

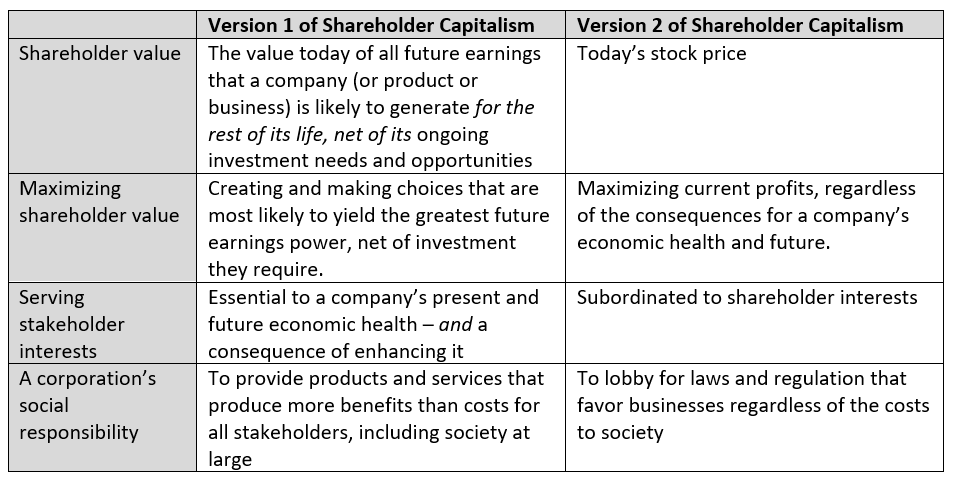

These are very different versions of shareholder capitalism, as summarized in this table:

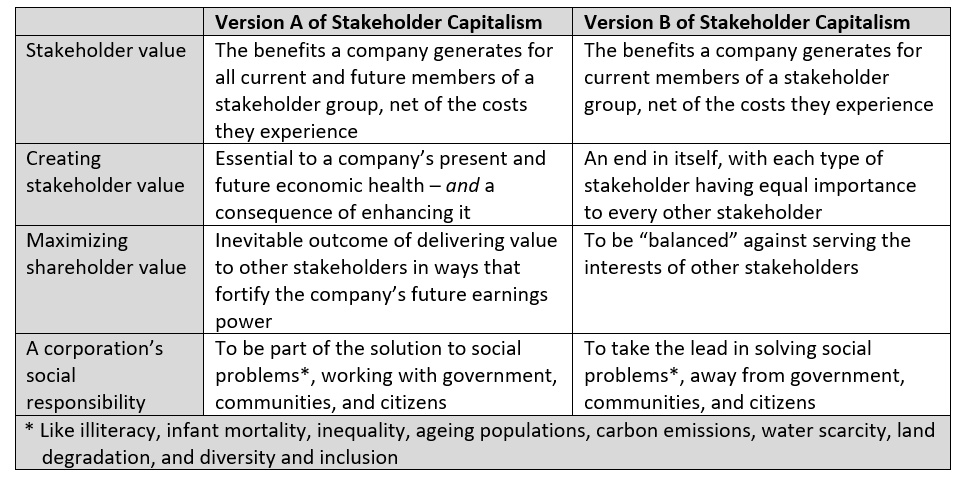

To further complicate matters, there are also two versions of “stakeholder capitalism” bandied about as well. One was adopted in 2006 by the UK Companies Act with the following guidance: “Corporate leaders are urged to pay close attention to how stakeholder factors affect long-term value maximization.” The other is expressed as follows: “Directors have a plurality of independent constituencies and must balance a plurality of autonomous ends.” This table compares these two versions:

For business leaders, the shareholder-stakeholder debate generates a lot of heat with little light because the protagonists on both sides rarely make clear which version of shareholder and stakeholder capitalism they are supporting or attacking in the two tables above.

For example, in July 2020, Presidential candidate Joe Biden said, “It’s way past time we put an end to the era of shareholder capitalism. [Companies] have responsibility to their workers, their community, to their country.” Was he talking about Version 1 or 2 of “shareholder capitalism?” Another example comes from The World Economic Forum. In January 2020 it came out with a manifesto urging companies to move to “stakeholder capitalism.” Is it advocating Version A or B?

The more business leaders put what they hear through the screen of the two tables above, the more they’ll be able to separate noise from signal. For example, consider the Business Roundtable (BRT). In August 2019, it published with great fanfare a proclamation on “The Purpose of a Corporation.” It was signed by 181 CEOs whose companies represented over one-third of the total market capitalization in the U.S. equity markets. The statement read, “We share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” which they list as customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders.”

Note the order. Because shareholders come last, pundits have loudly pronounced this as “ending shareholder primacy” (as Fortune described it) and “abandoning the shareholder-first mantra” (Financial Times). Or in other words, “shareholder capitalism” is dead and “stakeholder capitalism” is to take its place. But consider the following facts:

Fact 1: Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase and Alex Gorsky of Johnson & Johnson signed the BRT statement. Both are not only the CEO of their respective companies, but chairman as well. Moreover, Dimon was chairman of the BRT at the time its statement was issued and Gorsky chairs the BRT’s Corporate Governance Committee. Yet JP Morgan’s own corporate governance guidelines state very clearly that “the Board as a whole is responsible for the oversight of management on behalf of the Firm’s shareholders.” Likewise, J&J’s governance guidelines demand that “the business judgment of the Board must be exercised … in the … interests of our shareholders.”

Fact 2: In a previous proclamation, published in 1997, the BRT endorsed “maximizing shareholder value” as the governing objective of public companies. In that proclamation the BRT said, “It is in the long-term interests of stockholders…to treat its employees well, to serve its customers well, to encourage its suppliers to continue to supply it, to honor its debts, and to have a reputation for civic responsibility.” Now compare that to the list of five “commitments” included in the BRT’s August 2019 statement: “delivering value to customers, investing in employees, dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers, supporting the communities in which a company operates, and generating long-term value for shareholders.”

Fact 3: In an interview with The New York Times, the BRT’s current president, Joshua Bolten, said, “(Our proclamation) was not a demotion of … long-term shareholders, because, in our view, the interests of all stakeholders align in the long-run.”

Fact 4: The Managing Partner of the consulting firm McKinsey & Company is a signatory of the BRT’s August 2019 proclamation. In June 2020 his firm published an article in which the authors advised business leaders that “maximizing a company’s value to its shareholders, now and in the future” is a better objective than “simply maximizing today’s share price.”

Based on these four facts, which versions of shareholder and stakeholder capitalism is the BRT advocating? Leaders will have to form their own view. But they can safely assume that the BRT’s August 2019 proclamation is at the very least a repudiation of Version 2 of shareholder capitalism (see first table above), with its sharp emphasis on short-term profits, current stock price, and putting “shareholders first.” Leaders should reject that version, too. Simply making as much money as fast as possible won’t ensure that a company can flourish over time.

However, rejecting Version 2 of shareholder capitalism does not automatically mean a commitment to Version B of stakeholder capitalism (see second table above). Nor do the facts cited above suggest that this is the commitment the BRT is asking for.

To be sure, companies – especially the largest ones – are under pressure to be more responsive to their workers, communities, and the environment. And “maximizing shareholder value” often comes under fire when it’s associated with being the opposite of that. Sadly, if leaders want to rile certain politicians, journalists, academics, lawyers, or business leaders, all they have to do is say that companies should maximize shareholder value. That’s like waving a red rag to a bull. As Rajan Raghuram, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India said, “It sounds sinister – even if it may be the right thing to do...”

But the BRT probably knows that Version B is not the answer. It creates an impossible standard. Business leaders are endlessly confronted with tough decisions that involve unavoidable trade-offs between the competing interests of different stakeholders at any point in time. By supporting Version B, they make those decisions intractable and guarantee that they will politically shoot themselves in the foot sooner or later. For example, consider Marc Benioff, chief executive of Salesforce. To celebrate his quarterly earnings report in August 2020, he proclaimed, “This is a victory for stakeholder capitalism.” The very next day, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Salesforce informed 1,000 staff that their jobs were gone. When called out by The New York Times, all Benioff could muster in response was, “[Stakeholder capitalism] has to be viewed as both capturing an evolution and expressing an aspiration.”

Having rejected Version 2 of shareholder capitalism and most likely Version B of stakeholder capitalism, we are left with Versions 1 and A as the best characterization of the BRT’s position. The keen reader will notice that they are mirror images of each other. Two sides of the same coin. Ying and yang. Neither shareholder nor stakeholder capitalism. Just capitalism. The kind that has lifted mankind out of the primordial soup.

Nevertheless, the BRT’s proclamation is not the end of the great shareholder-stakeholder debate. It will never end as long as there is a short term and a long term, separation of ownership from management, and stakeholders – from shareholders to investment managers, stock analysts, customers, staff, unions, suppliers, governments, citizens, and “society” – who all want more from their companies, and now.

Ken Favaro is Chief Strategy Officer at BERA Brand Management.